Written by: Juan Tomás Pérez

Peru is the world’s third-largest copper producer, yet its artisanal and small-scale miners (ASM) remain virtually invisible in official statistics and disconnected from responsible supply chains. Official government data claims that artisanal copper mining accounts for just 0.2% of Peru’s production. The reality is far more complex: approximately 100,000 miners work in Peru’s copper sector informally, distributed across the southern regions of Apurímac, Huancavelica, and Ica. These miners operate within a fragmented global copper network characterized by stark geographic and economic separation between extraction nodes in Latin America and refining hubs in Asia. This fragmentation creates barriers to integration, making it difficult for downstream industries such as renewable energy companies, electronics manufacturers, and other copper-intensive sectors to source responsibly from Peruvian ASM. Multi-stakeholder initiatives (MSIs) have emerged as critical governance mechanisms to bridge these gaps, embedding artisanal mining within formal and responsible supply chains.

Understanding Fragmented Copper Supply Chains Through Global Production Network Theory

The global copper production network exemplifies the concept of fragmentation central to global production network (GPN) theory. Extraction occurs primarily in Latin America: Chile produces 24% of global copper led by State-owned Codelco and contributes 12% to national GDP, while Peru produces 12% and contributes 9.5-10% to GDP through three foreign-owned large-scale operations. Yet China, holding only 4% of copper reserves, controls 53-60% of global refining capacity and captures 25-35% of final copper value through subsidized smelters.

This geographic separation creates what scholars call “strategic coupling” challenges: actors at different stages of production operate with limited direct engagement, fragmented information flows, and power asymmetries that concentrate value capture at the refining and downstream consumption stages rather than upstream mining.

China’s dominance in refining, combined with leading consumption by renewable energy and electronics manufacturers concentrated in developed economies, leaves artisanal miners at the extraction end structurally disadvantaged. They have minimal bargaining power, face information barriers about downstream demands, and struggle to meet quality and compliance standards set by actors they never directly encounter.

Midstream refiners, operating at the smelting and refining stage across delocalized facilities, purchase copper concentrates from traders but have minimal visibility into their artisanal origins; similarly, downstream cable manufacturers depend on copper cathodes and wire rod from these refiners yet lack transparency into upstream ASM compliance, creating a structural disconnect where semi-formal Peruvian miners remain invisible despite supplying materials essential to the global energy transition.

GPN theory emphasizes three critical dimensions: value capture, power asymmetries, and embeddedness in governance systems. Copper flows from Peru to China for refining, then to downstream manufacturers, yet artisanal miners remain unembedded in formal governance structures that could guarantee fair terms, sustainable practices, or market access. MSIs can function precisely to reconfigure these networks, creating new governance platforms that embed ASM within responsible sourcing frameworks and redistribute information and power across fragmented production chains.

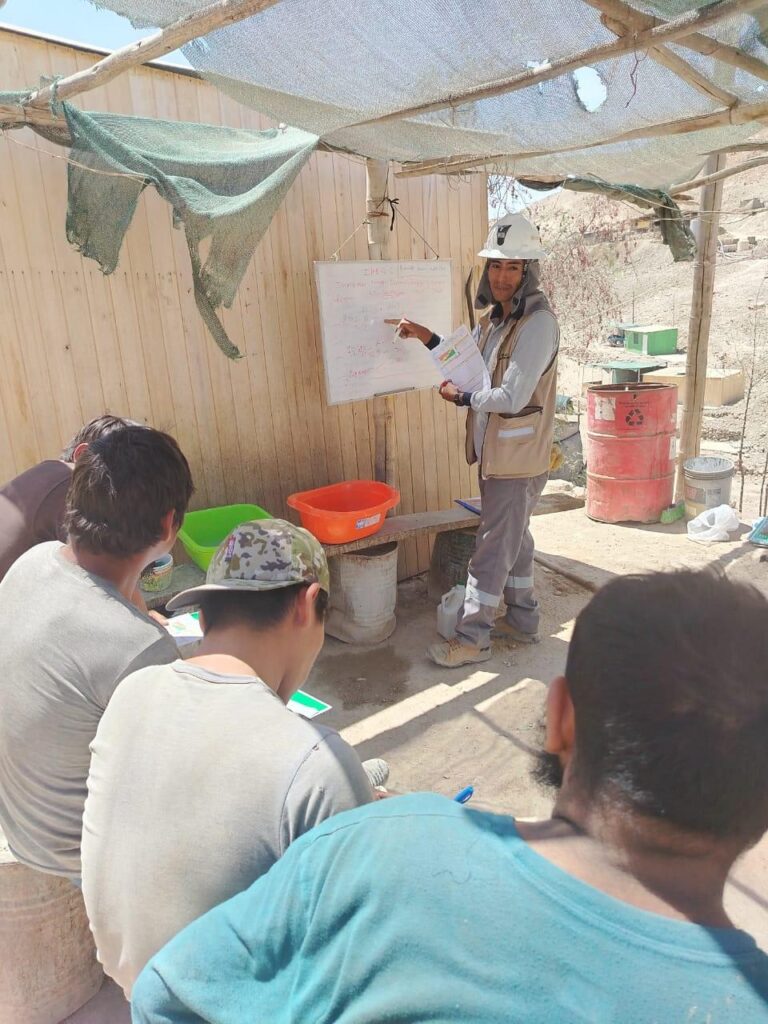

Tinguiña, Ica, Perú. Credits: Alliance for Responsible Mining

Understanding Peru's ASM Copper Mining Through a Formality Spectrum

Most analysis of ASM copper in Peru employs a binary categorization that obscures a more nuanced reality: the majority of Peru’s copper ASM miners operate in a semi-formal state, complying with certain regulatory requirements while failing to meet others. Rather than representing a transitional phase toward full formality, semi-formality characterizes the sector as a persistent feature shaped by structural constraints.

Under Peru’s formalization framework, ASM miners must satisfy multiple requirements: hold mining concessions or secure formal exploitation contracts, register in the Comprehensive Mining Formalization Registry (REINFO), conduct environmental impact assessments, pay taxes, and comply with labor standards. However, data reveals a complex mosaic of partial compliance. For instance, only 7.7% of registered REINFO miners hold mining concession titles; ~92% operate on concessions held by others, creating immediate legal obstacles to full formality. Of these, 27% work on concessions held by large scale or medium scale mining companies, while 73% work on titles held by other small-scale operators, many of whom are investors or speculators rather than active miners. This titling bottleneck renders “full formalization” literally impossible for most ASM miners, regardless of their willingness to comply.

Yet semi-formal miners engage in selective compliance: they may operate under provisional permits, register in REINFO (which 88,094 miners have done until July 2025), conduct simplified environmental impact declarations (IGAFOM) rather than full assessments, and attempt to align with some labor and safety standards—all while unable to achieve the paperwork completeness demanded by Peru’s extraordinary formalization process. More critically, semi-formal miners exist on a “formality continuum,” with heterogeneous configurations across the sector. Some comply with environmental requirements but lack proper tax registration; others secure provisional permits but operate without labor agreements; still others work informally with one buyer or invoicer while maintaining semi-formal relationships with others. This spectrum reflects not miners’ indifference to legality but rather a rational strategy from those who benefit from its persistence and the incompatibility between Peru’s regulatory framework and artisanal miners’ material realities.

Under these conditions, partial compliance represents a strategic equilibrium: miners demonstrate willingness to engage with regulation while maintaining operational flexibility in the face of an unreliable institutional environment.

Why Fragmentation and semi-formality Matter: Power, Value, and Governance Gaps

In fragmented copper networks, semi-formal ASM miners face compounded disadvantages. First, their ambiguous legal status excludes them from formal supply chains: downstream buyers and traders cannot credibly certify responsible sourcing if suppliers occupy legal limbo.

Second, semi-formality leaves miners vulnerable to enforcement discretion; they may face penalties, equipment confiscation, or sudden policy shifts despite demonstrating compliance intent.

Third, semi-formal miners cannot access formal financing, longer term commercial relationships, or quality premiums offered by responsible sourcing programs.

The copper concentrator plants that process ASM ore do so through intermediaries (acopiadores), invoice under their own names to obscure ASM origins, and retain valuable slag—a supply chain opacity that semi-formal status reinforces. Traders purchasing concentrate know little about their ultimate customers or the final end use of copper.

The Role of Multi Stakeholder Initiatives in Reconfiguring Copper Production Networks

MSIs such as the Copper Mark, Responsible Minerals Initiative (RMI), the IRBC Agreements and Alliance for Responsible Mining (ARM) serve as governance platforms reconfiguring fragmented production networks. These initiatives establish standardized due diligence criteria spanning environmental, labor, and human rights compliance. Criteria that traders, smelters, refiners, and manufacturers recognize and enforce across supply chains. Critically, MSIs create transparency mechanisms (traceability systems, supply chain mapping) that make semi-formal miners’ compliance visible and verifiable to downstream actors who previously had no assurance of responsible sourcing.

MSIs also function as capacity building bridges. Rather than imposing binary legality requirements, responsible sourcing initiatives recognize formalization as a process, establishing intermediate certifications and compliance pathways for semi-formal miners who demonstrate credible commitment and progress. By providing training, technical assistance, and second/third party verification, MSIs reduce information asymmetries and help semi-formal miners upgrade toward higher standards.

While MSIs function primarily through market mechanisms and private sector coordination, their effectiveness also depends on complementary government action and public sector alignment. Governments in mining nations like Peru must enforce formalization requirements, strengthen institutional capacity for supply chain oversight, and create regulatory frameworks that recognize progressive compliance pathways. Conversely, governments in refining and consuming countries can leverage procurement policies and due diligence regulations (e.g. EU’s Battery Regulation and Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive) to mandate traceability and responsible sourcing requirements that reinforce MSI standards. When public actors align with multi-stakeholder initiatives through complementary policies, they transform MSI certification from voluntary market differentiation into baseline compliance requirements.

From Exclusion to Integration: Concrete Actions for Midstream and Downstream Actors

For Midstream Traders and Concentrators:

- Commit to supply chain traceability extending to artisanal origins by implementing minerals reporting documentation systems (CMRT/EMRT) and mapping upstream mining sites and operators;

- Join MSIs as upstream participants, demonstrating commitment to responsible sourcing and creating contractual documentation of compliance;

- Work with semi-formal miners as legitimate stakeholders rather than evasion risks by offering technical assistance for formalization, conducting simplified due diligence assessments, and paying formalization premiums for documented compliance.

For Smelters and Refiners:

- Achieve and maintain third party certification (Copper Mark, RMI RMAP) by implementing comprehensive supply chain due diligence and documenting all upstream suppliers through CMRT/EMRT systems;

- Co-invest with upstream miners in traceability infrastructure, providing technical assistance, training in documentation systems, and support for environmental and labor compliance upgrades that enable semi-formal miners to achieve CRAFT Code compliance.

For Downstream Manufacturers and Renewable Energy Companies:

- Join RMI’s Downstream Assessment Program (DAP), creating contractual commitment to purchase only from RMAP conformant refiners and establishing competitive market advantage for responsible sourcing;

- Require suppliers to complete CMRT/EMRT documentation showing upstream sourcing; cross reference supplier names against Copper Mark and RMI conformant smelter lists before awarding supply contracts;

- Extend multi-year purchase agreements with compliant refiners at price premiums or guaranteed volumes, stabilizing markets and creating incentives for upstream investment in semi-formal ASM integration and formalization support.

Conclusion: Reconfiguring Copper GPNs for Inclusive Development

Fragmentary global copper production networks leave artisanal miners structurally disadvantaged. Yet semi-formal ASM copper miners in Peru represent not a regulatory failure to be erased but an economic and social reality demanding governance innovation. Multi stakeholder initiatives, by embedding semi-formal miners within transparent, standardized responsible supply chains, reorient fragmented production networks toward inclusion, value distribution, and sustainable livelihoods. Success requires upstream commitment from midstream and downstream actors: MSI participation, traceable sourcing, and recognition of semi-formality as a legitimate pathway toward responsible copper supply chains for the global energy transition.

This blog post was developed as part of a project funded by the European Partnership for Responsible Minerals (EPRM). The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the official position of the EPRM or its member organizations.

References

- Coe, N. M., Dicken, P., & Hess, M. (2008). Global production networks: Realizing the potential. Journal of Economic Geography, 8(3), 271–295. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbn002

- Coe, N. M., Dicken, P., & Hess, M. (2008). Introduction: Global production networks—debates and challenges. Journal of Economic Geography, 8(3), 267–269. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbn006

- Coe, Neil M., and Henry Wai-chung Yeung, Global Production Networks: Theorizing Economic Development in an Interconnected World (Oxford, 2015; online edn, Oxford Academic, 21 May 2015), https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198703907.001.0001

- Franken, G., Schütte, P. Current trends in addressing environmental and social risks in mining and mineral supply chains by regulatory and voluntary approaches. Miner Econ 35, 653–671 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13563-022-00309-3

- Responsible Minerals Initiative. RMI assessments introduction, Responsible Minerals Initiative. Available at: https://www.responsiblemineralsinitiative.org/responsible-minerals-assurance-process/

- International Copper Study Group. (2025). World Copper Factbook 2025. Available at: https://icsg.org/copper-factbook/.